PPMD is often asked the question: Can girls have Duchenne?

There are a number of Facebook groups focused on female carriers. Discussions and questions arise around why some female carriers of Duchenne have symptoms while others do not. Because Duchenne is primarily a diagnosis of boys, primary care providers (pediatricians) often do not consider it when they are trying to figure out why little girls are weak, have speech delays, or issues with balance. PPMD is trying to change this story by raising awareness about females with dystrophinopathy.

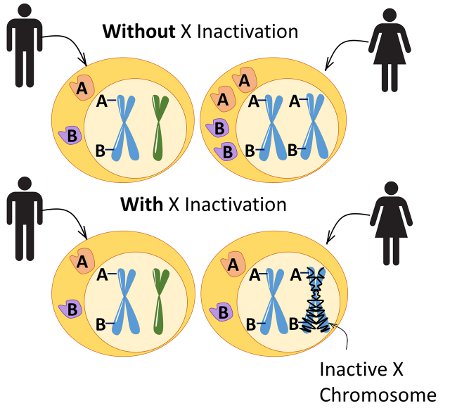

The dystrophin gene is located on the X-chromosome. Because boys only have only one X-chromosome (and one Y-chromosome), they will have Duchenne if there is a mutation in the dystrophin gene. However, girls have TWO X-chromosomes, which means they have TWO dystrophin genes. Being a carrier of Duchenne means they “carry” the mutation of the dystrophin gene on ONE of their X-chromosomes.

Typically, female carriers of Duchenne do not have symptoms because their “healthy” dystrophin gene takes over, and their body “turns off” their affected dystrophin gene. However, for reasons we do not yet understand, sometimes the “healthy” dystrophin gene may not work efficiently or at all and the body opts to use the affected dystrophin gene. This leads to females having similar symptoms (skeletal, cardiac, cognitive) as those with Duchenne and Becker, commonly termed “manifesting carriers.”

The process of X-chromosomes “turning off” is known as X-inactivation. It is common practice for neuromuscular specialists to order X-inactivation testing to try and understand why symptoms are happening in female carriers. However, we have learned X-inactivation testing is not accurate because X-inactivation can vary among muscle groups, causing symptoms such as one leg being weaker than the other. Dr. Nelson, a geneticist from UCLA, suggests that clinical symptoms, rather than X-linked inactivation testing, are currently the most appropriate way to assess whether a female is, or will be, a manifesting carrier.

Furthering the Discussion

We have been hearing stories of girls with Duchenne for a long time, learning about struggles receiving a diagnosis, lack of specialized care, and exclusion from scientific studies and clinical trials. PPMD’s Annual Conference includes a pre-conference meeting which is dedicated to an important topic or gap. This year, we focused on young female carriers who exhibit skeletal muscle symptoms early, before puberty.

We were joined by mothers of young girls with obvious skeletal muscle weakness, adult women who began showing symptoms at a young age, clinicians who care for young female carriers at PPMD’s Certified Duchenne Care Centers (CDCC) and academics who are invested in studying female carriers. One of the interesting questions was “what are we carrying” and a discussion about the term “manifesting carrier,” setting the stage for the discussion of females with dystrophinopathy, which we think better describes this population.

We learned there is a wide spectrum of symptoms experienced by these girls including muscle weakness and cramps, altered balance, fatigue (feeling tired), cardiac changes, and cognitive and behavioral issues (i.e. ADHD, learning disabilities, etc.). The participating clinicians agreed that earlier detection may lead to earlier and better treatment of symptoms.

However, testing female first-relatives of people living with Duchenne who are unable to legally consent remains a family decision. PPMD advocates for better education about the potential health risks of being a carrier of Duchenne. In addition, we suggest neuromuscular providers should ask parents about any potential symptoms seen in their young daughters. Should symptoms be identified, then a follow-up with CK testing and genetic testing is recommended.

The participants of this meeting also discussed potential guidelines for the care of young females with dystrophinopathy. Similar to males, females should be treated based on symptom severity. Those having symptoms such as fatigue, weakness or difficulties with balance should be seen every six months at a comprehensive neuromuscular clinic, preferably a Certified Duchenne Care Center, that will have all of the care and services needed. Those with cognitive issues should be referred for further evaluation and follow up.

Currently, females are not included in clinical trials or studies, including those investigating natural history. In response to this meeting, the ImagingDMD team at the University of Florida is planning to expand their protocol to include females with early skeletal muscle weakness, which will initiate a natural history study of young females with dystrophinopathy that are referred through PPMD’s Certified Duchenne Care Centers. To be notified of potential research opportunities for young females with dystrophinopathy, be sure to enroll in The Duchenne Registry.

We are optimistic these discussions among experts in the field will continue to drive improvements in the diagnosis, care, and awareness of females with dystrophinopathy. For more information about caring for carriers, please visit our website. If you have questions about your genetics report, or would like information about our free genetic testing program, Decode Duchenne, please call 888-520-8675 or email decode@parentprojectmd.org.

by: Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy

by: Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy